The Greatest Animal War

BY BROOKE BOREL / ILLUSTRATIONS BY KATIE SCOTT

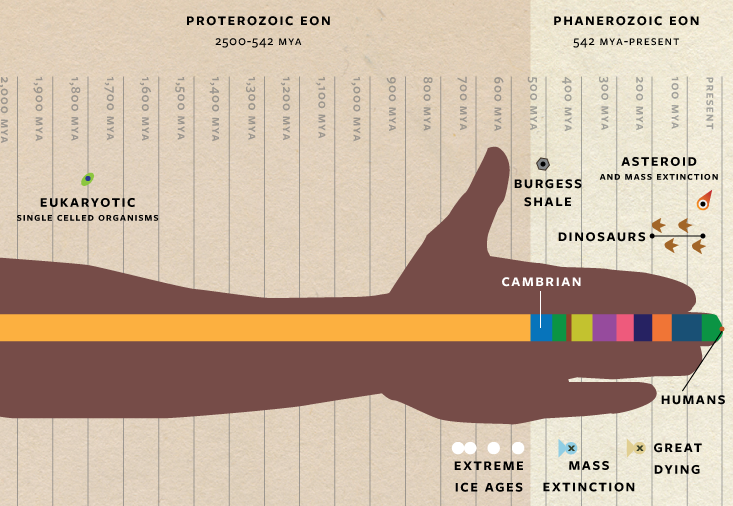

A simple species count does not do justice to the power of the Cambrian Explosion. Species have continuously formed over time. A new type of moth may have antennae that are furrier than its sisters; a new species of dinosaur may be distinguished by clawed wings and vicious front fangs. But a new phylum—a major branch on the tree of life, the upper-level ranking that separates an insect from a pterodactyl—is rarely born.

Most of today’s 30 to 40 animal phyla originated in the Cambrian, and have persisted through time with hundreds of variations on a theme (see Explosion). Where the Cambrian Explosion saw a proliferation of architectures (picture igloos, cabins, skyscrapers, suburban houses, and grass huts), the rest of time has mainly been about remodeling existing forms (add a Jacuzzi, a deck, or a tin roof). The explosion of animal phyla in the Cambrian includes the category, the chordates, to which humans, reptiles, sloths, and fish belong. Chordates are united by a central bundle of nerve fibers running down our backs, supported by a stiff rod.

Why did it take so long for the explosion to happen? After all, life arose 3.5 billion years ago, and the first eukaryotic cells (the kind within our bodies) occurred a billion and a half years later. Beneath the surface, a lot was probably going on: DNA had to work just right for organisms with multiple cells to evolve, and then enable a diversity of forms for natural selection to play with. In the Cambrian, “[animals] got large, and biomineralized, and they started doing stuff they never did before,” says Nick Butterfield, a paleontologist at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. “Suddenly,” he says, “it just started to click.”