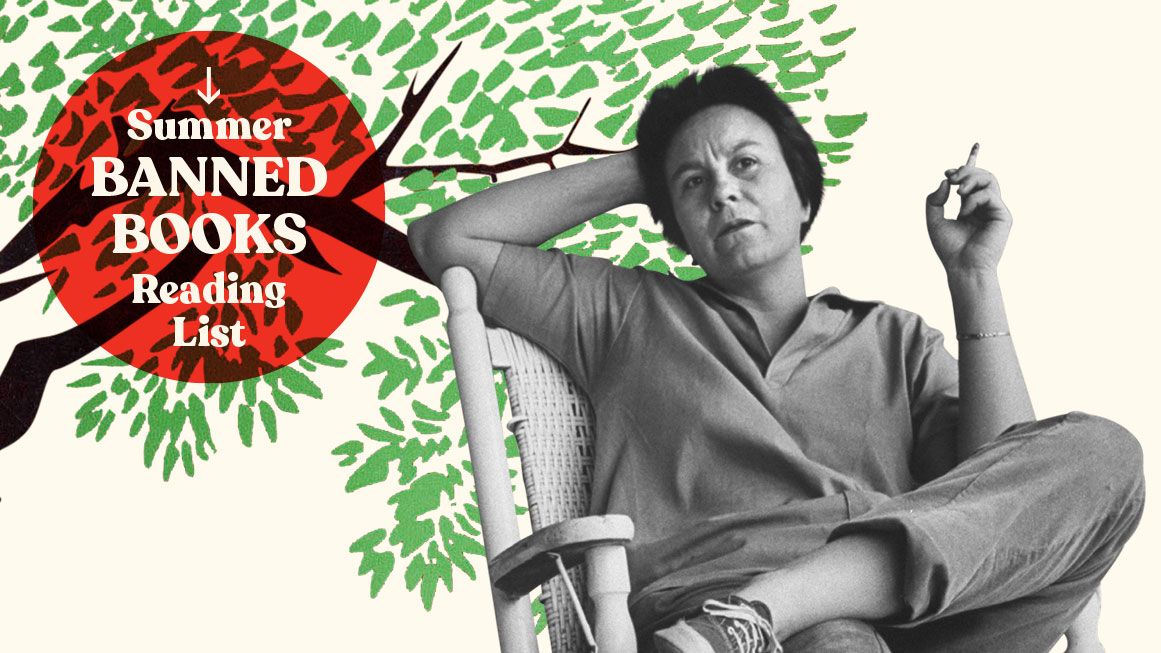

The Failed Campaign To Kill To Kill a Mockingbird

Recent moves to censor the book have come from Virginia, Mississippi, and California.

People have been trying to ban Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird since the 1960s. And since the 1960s, they have largely failed. In one early instance, the school board of Virginia’s Hanover County unanimously voted in 1966 to remove the book after board member W.C. Bosher found his son, a high school junior, reading it. The board gave little reason for the decision other than Bosher calling the book “immoral” and “improper for our children.”

Letters to a local newspaper supporting removal focused on the book’s discussion of rape, wherein white Atticus Finch defends black Tom Robinson in court from a false accusation by a white woman. Lee herself compared the criticism to “doublethink” in George Orwell’s novel 1984 (which the board also removed), yet she wrote that the “problem is one of illiteracy, not Marxism” and sent a check to be put toward a first-grade education for the school board.

Today, campaigns against the book frequently focus on its use of the word nigger. Characters (mostly white ones) use the word 48 times, because that’s how many people talked in 1930s Alabama. The word gets pushback in the book on at least two occasions. When young Scout Finch asks what “nigger-lover” means, her father Atticus says: “Ignorant, trashy people use it when they think somebody’s favoring Negroes over and above themselves. It’s slipped into usage with some people like ourselves, when they want a common, ugly term to label somebody.”