The Island That Humans Can’t Conquer

A faraway island in Alaska has had its share of visitors, but none can remain for long on its shores.

Text by Sarah Gilman / Photos by Nathaniel Wilder

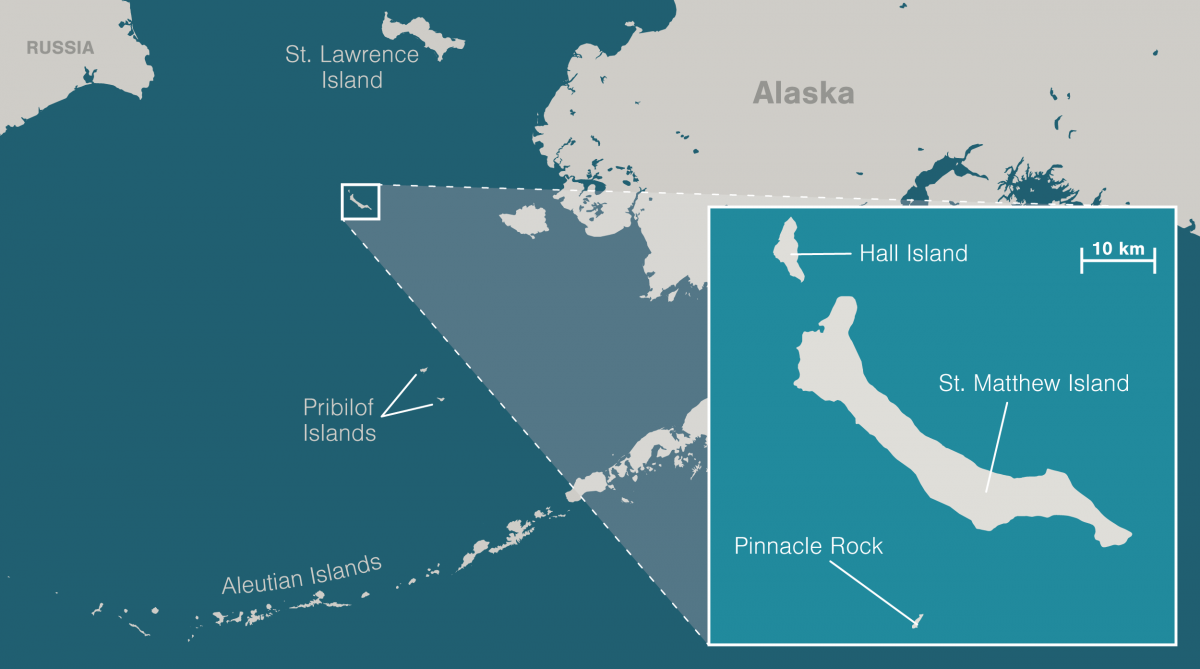

St. Matthew Island is said to be the most remote place in Alaska. Marooned in the Bering Sea halfway to Siberia, it is well over 300 kilometers and a 24-hour ship ride from the nearest human settlements. It looks fittingly forbidding, the way it emerges from its drape of fog like the dark spread of a wing. Curved, treeless mountains crowd its sliver of land, plunging in sudden cliffs where they meet the surf. To St. Matthew’s north lies the smaller, more precipitous island of Hall. A castle of stone called Pinnacle stands guard off St. Matthew’s southern flank. To set foot on this scatter of land surrounded by endless ocean is to feel yourself swallowed by the nowhere at the center of a drowned compass rose.

My head swims a little as I peer into a shallow pit on St. Matthew’s northwestern tip. It’s late July in 2019, and the air buzzes with the chitters of the island’s endemic singing voles. Wildflowers and cotton grass constellate the tundra that has grown over the depression at my feet, but around 400 years ago, it was a house, dug partway into the earth to keep out the elements. It’s the oldest human sign on the island, the only prehistoric house ever found here. A lichen-crusted whale jawbone points downhill toward the sea, the rose’s due-north needle.

Compared with more sheltered bays and beaches on the island’s eastern side, it would have been a relatively harsh place to settle. Storms regularly slam this coast with the full force of the open ocean. As many as 300 polar bears used to summer here, before Russians and Americans hunted them out in the late 1800s. Evidence suggests that the pit house’s occupants likely didn’t use it for more than a season, according to Dennis Griffin, an archaeologist who’s worked on the archipelago since 2002. Excavations of the site have turned up enough to suggest that people of the Thule culture—precursors to the Inuit and Yup’ik who now inhabit Alaska’s northwestern coasts—built it. But Griffin has found no sign of a hearth, and only a thin layer of artifacts.