Newspaper Cartoonists Rely on Digital Tools, but Not as You’d Expect

I spent dozens of hours last fall interviewing newspaper cartoonists about how they draw their work, assuming that many would have adopted modern tools like a Wacom Cintiq tablet or at least a digital stylus paired with something like an iPad. Instead, I was surprised to find that many rely on traditional media, like ink, paint, and watercolor. Even more surprising? Many younger artists, who had the choice of whether to start in analog or digital, work on paper instead of on screen.

I expected that most artists producing daily cartoons would have made a partial or total conversion to drawing and producing their work digitally, thanks to the advantages in time and effort. Perhaps those who started working before the 1990s would largely stick to traditional media, but I reckoned even some percentage of them would have shifted over. But no. While they don’t draw digitally, they’re happy to leverage digital technologies in other ways.

The persistent use of liquid stuff on paper is partly because modern reproduction technology makes it just as easy to work in older media as with digital tools. The ease of scanning, or even taking high-resolution flat photos of analog work, outweighs the seeming advantages of an all-digital workflow for those who prefer the messy, unpredictable, and sometimes frustrating limitations of materials for the physical feedback, happy accidents, and familiarity they provide.

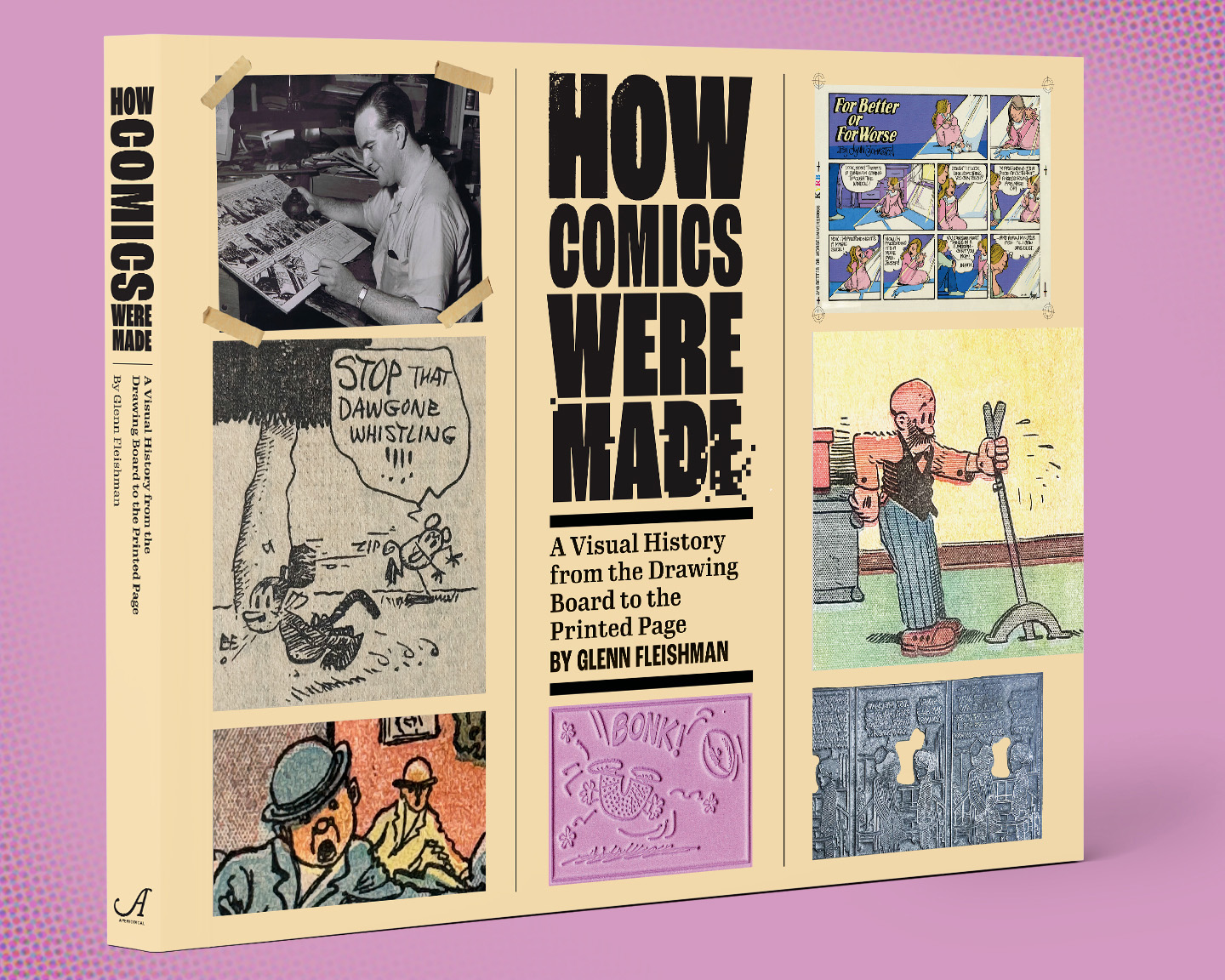

These interviews were part of my multi-year research for a book, How Comics Were Made: A Visual History from the Drawing Board to the Printed Page, that I’m currently crowdfunding with an anticipated ship date late in 2024. My book starts in the 1890s and follows North American newspaper comic production and reproduction to the modern days, focusing on how artists drew their strips and worked their way through the transformations necessary to get artwork onto a newsprint page or digital display.