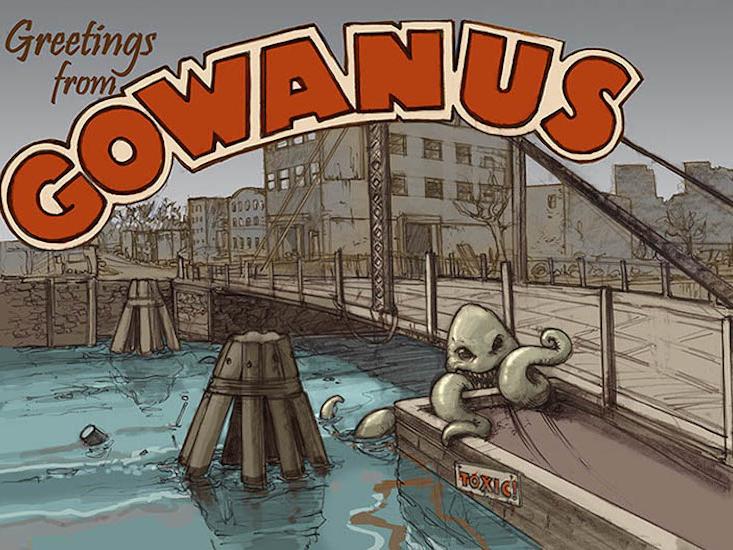

In the “Black Mayonnaise” of Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, Alien Life Is Being Born

POSTED BY TYLER J. KELLEY

Illustration by Simon Fraser/Eugene Lehnert

Illustration by Simon Fraser/Eugene Lehnert

On a late fall morning, Joseph Alexiou fastened his life jacket and stepped into an eight-foot fiberglass boat floating on the Gowanus Canal. A licensed New York City tour guide, and an amateur historian, Alexiou was preparing to take a passenger on an unsanctioned tour of the waterway he’d spent three years researching for his book, Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal. Alexiou, 32, confessed that when boating on the canal, he felt slightly afraid for his life.

The rowboat pulled away from the rubble at the foot of Second Avenue, beside the new Brooklyn parole check-in office and across from Whole Foods Market. The water was milky green, with an almost oily thickness, and gangs of loose lumber blew crosswise in the wind. Alexiou took a picture of graffiti that said “Keep Gowanus dirty.” Then he began to rattle off, with apparent encyclopedic accuracy, the history of every building in sight.

In the 1800s, Brooklyn’s manufactured gas industry, which turned coal into gas (illuminating the city before electricity), had facilities along the Gowanus and became a major culprit in the colossal pollution of the 1.8-mile long canal. What’s more, the canal has always been a wetland, alternately draining and flooding the surrounding area. During heavy rain, untreated sewage pours into it from several points, the result of New York’s combined sewer and storm drain system and the canal’s low elevation. “Only the monumental, astronomically expensive effort of engineering could change this fact of geography, and so during the greatest rainstorms, swelling tidewaters fill the main and lateral sewer pipes,” Alexiou wrote in Gowanus. “Once these are full, the waters fill area basements—a fact of nineteenth-century life that continues today.”

In 2010, the canal was declared a Superfund site, authorizing the Environmental Protection Agency, and other government agencies, to clean it up. More than $500 million has been requested to combat 150 years of pollution. If you fell in, Alexiou said, you’d be treading in human feces and shower water. If you touched bottom, he added, you’d be stepping in “coal tar, PAH, PCBs, and heavy metals like cadmium, lead, and mercury—they call it black mayonnaise.”