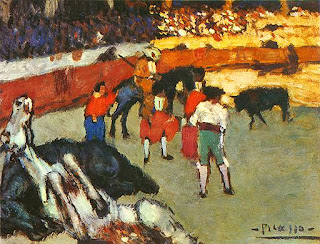

Bullfighting is seen by many as cruel. But it is not merely a gaudy circus spectacle; at its best it is an art form. Can aesthetics justify the suffering of the animal?

Alexander Fiske-Harrison

The following events occurred on 19th April 2007, the second day of the Feria de Abril in Seville, in the Plaza de Toros de la Real Maestranza de Caballeria

The bull enters the ring at a trot, a fanfare of trumpets fading in the background. He seems tentative, his eyes sweeping the ring.

The bull enters the ring at a trot, a fanfare of trumpets fading in the background. He seems tentative, his eyes sweeping the ring.

His breeders have named him Borgoñés. He arrived in town the night before from the pastures of Victorino Martin’s estate in west-central Spain, 50 miles from the Portuguese border. Here, on this mix of pasture, scrub and woodland, Borgoñés learnt how to use his horns on other bulls and built his 86.5 stone bulk of muscle and bone. Now that he is alone for the first time in his life, the restraints on his more ferocious instincts have been removed.

Standing at the far edges of the circular ring, some 60 yards from the bull, are three banderilleros: companions and employees of the matador in lesser versions of his “suit of lights,” each with a large working cape in his hands, pink on one side, yellow on the other. They flap their capes from the safety of wooden hides in the barrier of the ring until Borgoñés charges across the ring, selecting his target. The  bull does not stop until he hits the wall of the wooden hide, the man safely behind as Borgoñés jabs again and again at the wood, splinters flying. Borgoñés has shown that he is quick to take the lure, that he charges straight, without hesitation or pawing the ground, and that he favours his right horn.

bull does not stop until he hits the wall of the wooden hide, the man safely behind as Borgoñés jabs again and again at the wood, splinters flying. Borgoñés has shown that he is quick to take the lure, that he charges straight, without hesitation or pawing the ground, and that he favours his right horn.

The matador walks into the ring, an unprepossessing 33-year-old man of neat figure and composed manner. Manuel Jesús Cid Salas, or “El Cid,” was born in a small town on the outskirts of Seville called Salteras. He flaps his cape and the bull turns, raising his great head with its wide-ranging horns so that the vast goring muscle, the morillo, bunches on its shoulders to a size outstripping any other breed of bull in the world. And then he charges. Unlike his cuadrilla, his group of companions, El Cid does not hide but stands his ground, his back ramrod straight, the cape held out to the right of his body in both hands, feet together, and waits for Borgoñés to come to him. Borgoñés is fresh, the distance is sizeable, and the bull nears 30 miles per hour as he reaches El Cid. El Cid moves the cape slightly, and Borgoñés takes the moving lure over the stationary man and thunders past, his horns low where the movement was, the cape sweeping over his face in a perfect veronica, named after the saint of the same name who wiped the face of Christ on his way to Golgotha.

Borgoñés comes out the other side, frustrated that his horn met no opposition, and turns within two body lengths of passing El Cid, who has readjusted his own position to receive Borgoñés in another veronica, as neat as the first, the horns passing some 18 inches from El Cid’s face as Borgoñés leaps into the air when he reaches the cape, trying again to sate his rising fury in living flesh. The crowd, already impressed by the first veronica, shout an “olé!” for the second. Again Borgoñés passes the man by, again the crowd roars, again Borgoñés turns, again he passes, a foot away from the man this time, and he turns again, comes back and this time El Cid winds the cape around his own hips as Borgoñés follows it, winding the bull around his body in a media-veronica. For a brief moment, following the increasing display of risk and skill in the veronicas, we are given the sight of the man, stationary, in the midst of a circling fury, wearing this great beast like a belt, the crowd cheering, until Borgoñés, driven by his own momentum out of the charge, is drawn to a halt by attempting to turn in a distance shorter than his own body length. He is left panting, facing El Cid three yards away, who is standing with his back to the bull. El Cid receives his applause from the crowd and thus ends the section called suerte de capote, “luck of the cape,” the first half of the first act of the bullfight called the tercio de varas, the “third of the lances.”

Borgoñés comes out the other side, frustrated that his horn met no opposition, and turns within two body lengths of passing El Cid, who has readjusted his own position to receive Borgoñés in another veronica, as neat as the first, the horns passing some 18 inches from El Cid’s face as Borgoñés leaps into the air when he reaches the cape, trying again to sate his rising fury in living flesh. The crowd, already impressed by the first veronica, shout an “olé!” for the second. Again Borgoñés passes the man by, again the crowd roars, again Borgoñés turns, again he passes, a foot away from the man this time, and he turns again, comes back and this time El Cid winds the cape around his own hips as Borgoñés follows it, winding the bull around his body in a media-veronica. For a brief moment, following the increasing display of risk and skill in the veronicas, we are given the sight of the man, stationary, in the midst of a circling fury, wearing this great beast like a belt, the crowd cheering, until Borgoñés, driven by his own momentum out of the charge, is drawn to a halt by attempting to turn in a distance shorter than his own body length. He is left panting, facing El Cid three yards away, who is standing with his back to the bull. El Cid receives his applause from the crowd and thus ends the section called suerte de capote, “luck of the cape,” the first half of the first act of the bullfight called the tercio de varas, the “third of the lances.”

El Cid has now learned that Borgoñés is a bull truly in the prime of life, possessed of speed, strength, stamina and courage, but without the excessive aggression which would make him unpredictable and self-destructive. He has sufficient intelligence to follow the cape in these moves—which have been refined over 250 years—but not so much that he has learnt to distinguish man and cape early in the fight. This bull, after all, has probably never seen a man on the ground before, his herdsmen on the estate all being mounted on horseback. However, he is learning. At some point he will, inevitably, see the man.

El Cid has now learned that Borgoñés is a bull truly in the prime of life, possessed of speed, strength, stamina and courage, but without the excessive aggression which would make him unpredictable and self-destructive. He has sufficient intelligence to follow the cape in these moves—which have been refined over 250 years—but not so much that he has learnt to distinguish man and cape early in the fight. This bull, after all, has probably never seen a man on the ground before, his herdsmen on the estate all being mounted on horseback. However, he is learning. At some point he will, inevitably, see the man.

[ click to continue reading at prospect-magazine.co.uk ]

Discuss this piece at First Drafts, Prospect‘s blog