Ian Thomson reviews a collection of Malcolm Lowry’s poems, letters and fictions

Malcolm Lowry was a ferocious malcontent, who free-wheeled towards an early grave with the help of cooking sherry, meths, even bottles of skin bracer. From skid row to bedlam and back, it was a Faustian dissipation. Lowry died in 1957, at the age of 48, from an overdose of barbiturates, having written his epitaph:

Malcolm Lowry was a ferocious malcontent, who free-wheeled towards an early grave with the help of cooking sherry, meths, even bottles of skin bracer. From skid row to bedlam and back, it was a Faustian dissipation. Lowry died in 1957, at the age of 48, from an overdose of barbiturates, having written his epitaph:

Malcolm Lowry

Late of the Bowery

His prose was flowery

And often glowery

He lived, nightly, and drank, daily,

And died playing the ukulele.

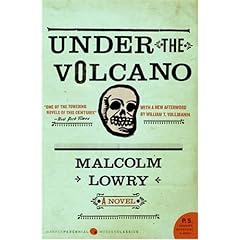

His reputation rests on one novel only: Under the Volcano (1947). Set in Mexico on the Day of the Dead, it describes the last 24 hours in the life of Geoffrey Firmin, HM ex-Consul, as he drowns in liquor and despair under the shadow of Popocatepetl. Lowry’s genius was to transform Firmin’s shabby addiction into a parable of universal significance and the story of Everyman in search of salvation. The novel’s mescal-inspired grotesqueries — grinning chocolate skulls and twitching centipedes — seemed to issue from the charnel-house of Baudelaire’s imagination. For all his modernity (Kafka and T. S. Eliot were clear influences), Lowry wrote in the timeless tradition of the damned poet who sees a holiness in going down the drain.

Like many alcoholics, Lowry is a murderous subject for biographers: not only could he make the wildest nonsense about himself credible, he encouraged others to add to it. Originally his biography was to have been written by the Canadian scholar Conrad Knickerbocker (a fine Lowryesque name); but, in 1966, Knickerbocker committed suicide. Another critic, Douglas Day, brought out his life of Lowry in 1973: it was marred by psychoanalytical humbug and factual errors. Gordon Bowker, Lowry’s most trustworthy exegete, published his compelling biography, Pursued by Furies, in 1993; it is unlikely to be surpassed.

Like many alcoholics, Lowry is a murderous subject for biographers: not only could he make the wildest nonsense about himself credible, he encouraged others to add to it. Originally his biography was to have been written by the Canadian scholar Conrad Knickerbocker (a fine Lowryesque name); but, in 1966, Knickerbocker committed suicide. Another critic, Douglas Day, brought out his life of Lowry in 1973: it was marred by psychoanalytical humbug and factual errors. Gordon Bowker, Lowry’s most trustworthy exegete, published his compelling biography, Pursued by Furies, in 1993; it is unlikely to be surpassed.

In many ways, Lowry’s life was his own finest creation. All his writing — three unfinished novels, six or seven short stories, hundreds of letters and poems — was thinly veiled autobiography. According to Michael Hoffmann, Lowry intended the ‘whole bolus’ to be part of a continuum called The Voyage that Never Ends, with the great Mexican novel at its centre. Only fragments of this Dantean scheme remain, but the novella Lunar Caustic, begun in 1935, was to represent purgatory. (It was based on Lowry’s internment in the Bellevue mental hospital, New York.)

[ click to read full article by Ian Thomson in The Spectator ]