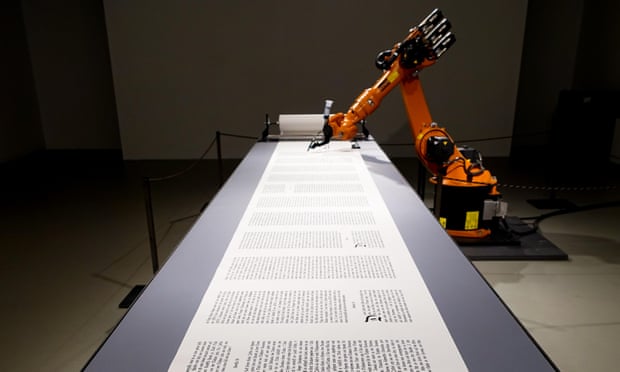

The rise of robot authors: is the writing on the wall for human novelists?

Artificial intelligence can now write fiction and journalism. But does it measure up to George Orwell – and can it report on Brexit?

by Steven Poole

Will androids write novels about electric sheep? The dream, or nightmare, of totally machine-generated prose seemed to have come one step closer with the recent announcement of an artificial intelligence that could produce, all by itself, plausible news stories or fiction. It was the brainchild of OpenAI – a nonprofit lab backed by Elon Musk and other tech entrepreneurs – which slyly alarmed the literati by announcing that the AI (called GPT2) was too dangerous for them to release into the wild, because it could be employed to create “deepfakes for text”. “Due to our concerns about malicious applications of the technology,” they said, “we are not releasing the trained model.” Are machine-learning entities going to be the new weapons of information terrorism, or will they just put humble midlist novelists out of business?

Let’s first take a step back. AI has been the next big thing for so long that it’s easy to assume “artificial intelligence” now exists. It doesn’t, if by “intelligence” we mean what we sometimes encounter in our fellow humans. GPT2 is just using methods of statistical analysis, trained on huge amounts of human-written text – 40GB of web pages, in this case, that received recommendations from Reddit readers – to predict what ought to come next. This probabilistic approach is how Google Translate works, and also the method behind Gmail’s automatic replies (“OK.” “See you then.” “That’s fine!”) It can be eerily good, but it is not as intelligent as, say, a bee.

Right now, novelists don’t seem to have much to fear. Fed the opening line of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four – “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen” – the machine continued the narrative as follows: “I was in my car on my way to a new job in Seattle. I put the gas in, put the key in, and then I let it run. I just imagined what the day would be like. A hundred years from now. In 2045, I was a teacher in some school in a poor part of rural China. I started with Chinese history and history of science.”